earlier paintings

Yves Michaud

A view purified and renewed

The first works of Urmo Raus that I remember were small engravings obtained by the imprint of pieces of plexiglass which were pressed and burst under the press. Their colouring was black and grey run through with cracks, and which gave the impression of a controlled violence, an appeal to the viewer to concentrate on the twin event, the engraving and the breaking, but also on a kind of freezing of the external aspect.I also remember paintings which were quite large without being excessively so, black and grey, monochrome, the size of one's outstretched arms, with canvas that was worn, made fragile and scored by the repetition of gestures, of scratches and writing. There was a kind of ancient surface, prehistoric, collecting innumerable gestures, the added value of repetition and persistence. And yet, despite the risk of primitivism, this painting was not at the level of graffiti, or of a primitive design transferred to canvas. I would suggest that it had a powerful autonomy and that its existence, which was neither a report nor the transposition of motives from without, was in contrast to the work certain painters who use graffiti, or pick up primitive motifs at the level of universal signs. No, here surface, gesture, colour, scoring and accidents of production were all profoundly contemporary, I would even say caught in the same temporality of production, and the perception involved, becomes a unified pictorial object. It is for that reason that while one could think of an investigation into archaic material, this archaic quality was in fact an immediate presence of something immemorial and profoundly personal at one and the same time, and by no means an investigation into primitivism or archaicism.

Over time and with growing maturity, these qualities of immediacy and unity have not only been preserved but made more profound and in his recent paintings Raus has something remarkably touching, moving, things which bear witness to the concomitance of a solid painting technique with a strong presence evincing feeling and experience of life. Put it this way, here we read into the painting a surprisingly large measure of professionalism with an authenticity as well as personality and feeling. This would seem to me to be quite rare and it is this which gives these paintings their unusual strength.

I do not wish here to enter into expansive reflections on our present age, still less on the situation painting finds itself today, in an age where the end of painting has been proclaimed; that would be straying from the subject. Nor do I have the time to do so. I would simply like to say that I often have the impression that one of the difficulties of the age, for artists but not for them alone, is the constant oscillation between spontaneity and skill, between authenticity and technical competence, between experience and reflection. There is a strong urge towards immediacy and authenticity ("be yourself" is the universal expression for this quest) but it rests against a background of a lucidity that is quite cynical with regard to the limits of authenticity, also against a background of mastery and too easy games of conscience and reflection. At heart, we know all too well how to "be ourselves" and we have conscience of disillusion of this constructed authenticity.

Hence, in art, the vacillations between expressive naiveté and the awareness of this naiveté, between natural immediacy and the next degree, i.e. the curious distance which affects the expressions and techniques of many artists who do not wish to be regarded as fools or stupid.

What seems to me to be particularly interesting in the work of Urmo Raus is that he avoids this contemporary attitude of mind and manages to furnish proof of naiveté accompanied by a non-naVve form of expression - and I weigh up, in order to underscore the fact, the apparent contradiction in what I am saying. In his work there also lies a great awareness of painting, of its forms, its history. He also evinces the cosmopolitan experience of a young European, something he has acquired over the course of his apprenticeship in Estonia, France, Germany and the Netherlands. He is, therefore, quite cognisant of what is happening there and of the problems which arise. He knows all the tricks used there, ones which are currently in fashion. And yet he remains himself.

He remains himself, that is to say he remain himself in the experience of various aspects of nature, of the epoch, of feelings; he also remains himself with regard to the idea of painting, of abstraction and its relations to visual, aural and existential experiences. The empty, grey, metallic photographs which Urmo Raus takes from nature are illuminating indications of such experiences.

In a commentary on his own painting, he has mentioned how certain experiences from the cold and silent North, how certain experiences in life, of the family, also play their part in his art. He repudiates nothing of the "content" of these experiences, but at the same time he wishes to remain aloof to these in his painting, hence his method of subtraction, exhaustion, abstraction in the true and original sense of the word, depriving his painting its picturesque quality.

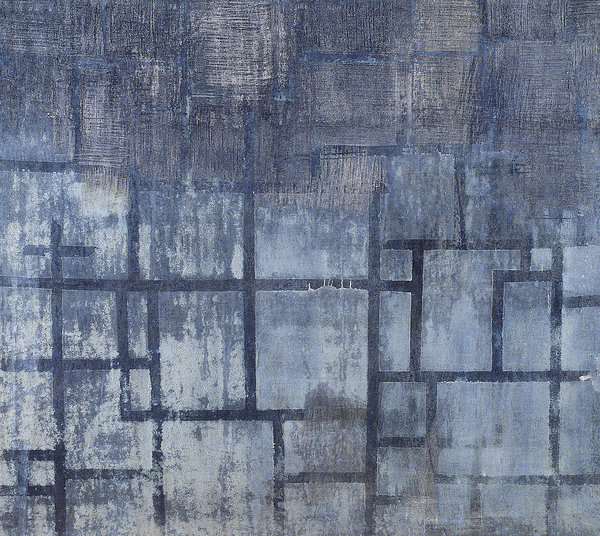

In the eighteenth century, there was a period during which pictorial effects, as well as particular subjects suitable for painting (rocks, forests, fields of light and shade, and the way of painting, led to a predominance of the picturesque, an over-reliance on technique at the expense of authenticity. This can be found in art where the depiction of gardens was anti-natural and where the picturesque found its full expression: painting had, in a sense, departed from itself. The critics of the picturesque, on the other hand, highlighted strictly pictorial values and, when all is said and done, formal ones. In actual fact, the conflict between these two points of view has never come to any resolution and it would even seem as if one of the keys to the painting of Urmo Raus is situated firmly within the orbit of the pictorial, but not in mechanical opposition, not appealing to abstraction versus picturesque - more a return to subtraction, purification, exhaustion. This is why he scratches, removes, takes away. What remains after the subject has been removed, when what is picturesque has been eliminated, is the canvas. And the same regarding colour. Raus does not use non-colours or industrial colours, in contrast to a number of young artists who, they too, want to escape from the picturesque nature of colour, or from historical connotations which are too boldly highlighted and which would set them in a "Modern" tradition. He uses earth, natural pigments, ochres, greys, blues, the colours of slate, brick and granite, and for this reason his painting combines the elements of nature. His paintings have the colours of the mud of the streets, of melting snow, causeways in the rain or sleet or the transparency of the clarity of moonlight, cold night colours, the blueness of ice.

Urmo Raus examines the scarcity of effects, but not on account of a poverty of vision. He examines limited numbers of effects, concentrated ones, ones which can call attention to themselves remain in the memory, setting the memory at rest. He rejects symbolism, even when simple forms such as rosettes, chords, diaphragms, bubbles and halos are present on the surface to effect differences and to produce an extended visual field. In this painting there is something approaching an attempt to cleanse ones eyes, to deprive perceptual apparatus saturated with images, making it a faculty of attention and of reception. There is no room for further attention and reception, nor is there an aim, an indication of other worlds. This painting is neither religious or in any way sacred. It does not sacrifice the laws of art, and of the eye, but addresses itself to concrete experience and a pared down

Aesthetics.

If there exists today a base upon which painting can continue to be reclaimed and defended, it is with the rules of concentration and with visual reception. This is somewhat analogous to the rules of poetry or music, defending us against the slogans of politics or advertising, against prepacked formul

F, or mood muzak or entertainment, making lifts more bearable to ride in. Urmo Raus belongs to those painters, poets and musicians who help us to rediscover free perception where we find again a moment of purity of feeling.

Paris, June 2, 2004

Anu Allas

The Memory and Materiality of Painting

Urmo Raus’s Paintings at the Tallinn Art Hall until December 14th.

Urmo Raus’s paintings seem to be speaking, and not only because his exhibition seemed to reveal some earlier period of Leonhard Lapin, some more modernist time period than the art of the last few decades. And yet, I would not call his works a reversal or a return to some definite stage in the past. Raus’s presence in today’s Estonian art – and especially the so-called visual culture scene – is a necessary stabilizer. In a situation where, in order to attract attention, one must offer as much as possible to as many as possible, assault all the channels and senses, the courage, even arrogance, to offer nothing more than non-pictorial gray canvases, and to do so on such a large scale, covering the entire exhibition surface on the upper floor of the Tallinn Art Hall, seems almost cathartic.

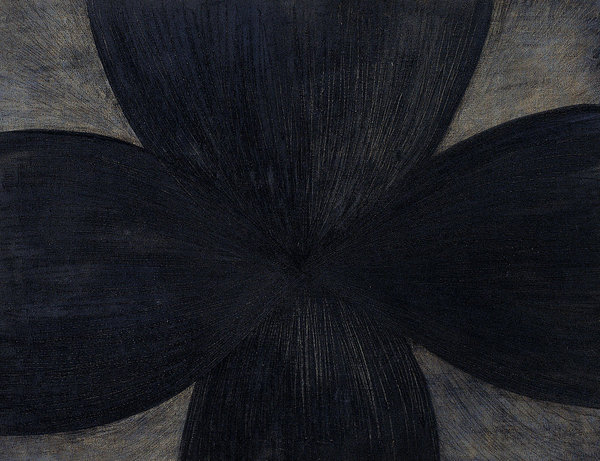

Compared to the previous ripped canvases, the paintings in this exhibition are more whole, with only small gashes and holes. And the prior uncompromising grey has now been mixed with muted shades of color. What stands out in the case of these sparse images is their twofold nature or continuity – two globes or kidneys that are side-by-side or merged together along one side, something resembling a tangled bunch of rope, streaks that cover the entire surface of the picture, etc. These pictures seem too ascetic for the emotional or literary approach that often accompanies abstract paintings, and are too immediate for a more conceptual approach. Even a certain feeling of protest develops: these paintings do not fit into any symbolism, do not express anything, although their physical presence is demanding and irrefutable.

Raus moves somewhere in the periphery, removing layer by layer, almost everything that has given painting its meaning, imagery, color, expressiveness, sensitive brush, etc. and then relents somewhat and does not allow the canvas to decompose totally. The scarcity of meaning coming from inside (or really from the surface of) the painting is also not balanced by any external, contextual framework. Raus is quite alone in today’s Estonian art scene and does not speak to any current event. This consistent renunciation turns its back on the challenging implications and emphatic self-awareness of postmodern painting. If upon cursory observation and against the surrounding background of pictorial trends, this renunciation seems to indicate the lack of something, actually it seems that that attention is being directed at the presence of something.

The meaning of paint and canvas in Raus’s works does not develop from how these tools are employed, or as an accompanying or additional value of something. The entire painting process (as it turns out from Raus’s descriptions of his work methods in interviews) is directed at the material as an equal opponent and not as a passive substance that requires inciting. A finely executed gesture of a creative genius alone is not enough to conquer the substance; rather the role of the artist is flexibility and adapting the random scratch to the direction of the paint flow and the opportunity to grasp onto them, to use them.

After the rapid dematerialization of art, the relationship between painting and its tools been more hesitant, arrogant, distanced. Apparently this is the reason why Raus’s sensitivity seems like a reversal, or even a re-materialization. Yet when viewing the works, one still perceives more of an abstract archaism than obvious preferences based on art history. This is the deepest layer, the physical being, primary energy that can be found in every painting ever painted, which has now been left without its superstructure. The canvas is stretched, the small cracks are still rough, the paint elemental, not applied or enriched, the images in a kind of embryonic state. If ripped canvases can be seen as post-pictorial, as having undergone some act of destruction, then these seem to be pre-pictorial. At times, Raus’s paintings seem to be located on one side of the fence where maturity, formality, and completion lie, and at other times on the other side; they are pictures before and after meanings. These canvases do not remember alternations, the changers in the grand tradition of painting, but continuity.

If Raus’s paintings are reminiscent of anything concrete, then is the view through a microscope. The relationship with one’s tools in the narrower (paint and canvas) and broader (painting art) sense seems to be that of a natural scientist rather than of a poet or philosopher. Raus does not deal with what something means, but examines what it is comprised of. What is left, after removing almost everything else? What are the minimum requisites of a painting, what are the paint and canvas, which has been allowed to express so much through the ages, but always something other than itself?

ANU ALLAS

19 December 2003 Sirp

Hanno Soans

About a Threadbare Painting

Urmo Raus’s latest solo exhibition in Estonia at the Vaal Gallery included three acrylic canvases, three monotypes and five drypoints on organic glass. The diploma from the École Nationale des Beaux Arts de Paris, which the newspapers loved to talk about in connection with the exhibition, was not on display. In his paintings, Raus has left the interpreter freedom and not provided a single guideline. We have arrived at a situation “in which the smallest gesture by the artists unleashes an avalanche of meaning.” While viewing Urmo Raus’s paintings, I was reminded of a quote by Johannes Saar about the main reason for the impactfulness of Jaan Toomik’s works. The connection is not incidental: both Toomik’s and Raus’s art are the results of sketchy gestures. Their works have a contemporary structure that jealously guards its cultural construction. I discover myself sometimes attributing natural origins to such art. Also the works of both artists can be characterized as the art of silence. The nullification of the media’s uninterrupted stream of eroticized signs provides the motivation for the creation of Raus’s paintings. A moment of silence is like a set of parentheses between which one can complete the thinking of one’s lost thoughts. In the uniformly spectacular hustle and bustle of society, the sovereignty of the paintings becomes an intensive experience. Toomik and Raus therefore continue to maintain a semiotic hunger strike. Energy must not be wasted on small talk. Compared to Toomik, Raus keeps his self-expressive supply of gestures more strictly in check. Raus keeps the art of painting in check.

“What would be the essence of a pair of trousers (if it has one)? Certainly not that carefully prepared and rectilinear object found on the racks of department stores; rather the ball of cloth dropped on the floor by the negligent hand of a young boy when he undresses tired, lazy and indifferent. The essence of an object has something to do with the way it turns into trash. It is not necessarily what remains after the object has been used, it’s rather what is thrown away in use. And so it is with Twombly’s writings.” This is how Roland Barthes described the writing on Cy Twombly’s paintings. And standing in front of Urmo Raus’s paintings almost twenty years later, I am repeating and adapting Barthes’s statement: “The essence of the art of painting is somewhat related to its destruction.” On these canvases we can see the obsession that has remained hidden throughout the history of painting – the traces of a hand that is skinning the canvas.

If some poetry has given up on dealing with that which is most typical of poetry – images, the sound of speech and words – then before its nullification, it clings to that which could be called the obsession of physical presence. Urmo Raus’s works also do no speak or depict. Like poetry holds onto paper, Raus’s paintings hold onto the canvas, and conventions help them remain there.

The calm presence of the works alludes to their completion. The process notifies and prioritizes, but in its details remains inaccessible to the viewer that is looking from frame to frame – the activity is overshadowed by the paintings. Unlike the creative logic of Abstract Expressionism, the artist also is overshadowed by the work. Namely, Raus does not celebrate the gestures that would declare the uniqueness of the creator’s presence, his cosmic freedom in regard to the created work. During the long work process, he separates the tragic theme of the painting from the basic materials. And as the tension increases and intensifies arriving at the end result, the artist has already left the arena.

Aufhebung as the leitmotif of Raus’s music

In Estonian painting, the Supilinn door series by Sven Saag is an earlier counterpart to Raus’s work. Each of the doors, which have been manually removed from their hinges by the artist, can be characterized as a nostalgically rambling sound bite, with the wistful patina of the teeming memories that are deposited in old objects and personal possessions. A sound background would also be needed for visualizing Raus’ paintings, because melancholy cannot be forced to answer us word for word. Raus’s palette is noticeably fresher than Saag’s. He creates the mood in his paintings with the help of subtle and cool coloring – rainy grey and snowy blue, and other closely related shades of color. The paintings are suited to Wim Mertens’s … no! actually Steve Reich’s early music. But I guess this is different for everyone.

It is difficult to think of a more worn out comparison than the synthetic parallel between the tonality of coloring and a musical sound image – but I could not find a fresher way of characterizing the being of Raus’s paintings. Raus’s character is too true to tradition for this.

Instead, it is important to mention that main motif of Raus’s music distances him from Saag – a nostalgic melancholy with a personal dimension (Wim Mertens) is present in Raus’s works only as a total negation of everything that is personal-sentimental, Aufhebung (Steve Reich).

Semioclasm in Raus’s work

It is not unwarranted to think that grimaces, improper words or some uncontrolled memory were initially painted on these canvases, which the artist decided to totally scrape off with admirable persistence. This would provide an explanation for the silent tension that has resulted. One can imagine that the scraping of the salacious illusionist deceit of the image or scribbling as the being the initial impetus for the violent creative act. Aggression as an idée fixe against the presented signs – semioclasm – appears perfectly at the point where art has been taken so close to its demise that the viewer is able to feel like a participant in the story of its birth.

The artist does not require a miscarried image to have been previously spread on the canvas, in other to sweep it away in the subsequent creative act of destruction. If it genuinely exists anywhere, it is in the head of the artist, but probably at a much deeper level that the weather reports of the conscious. The general hostility against a figurative, chatty visuality is fed by the societal monotony that is becoming ever more theatrical; from time to time, something in me also yearns for the fast that appears like a promise in Raus’s paintings.

Imagine the Art of Painting for a moment, as if it had been embodied in the historical consciousness as it appears in Urmo Raus’s works. To me, it seems to be an old, weird woman, a schizo, who, in the middle of the day, examines the pores on her cheeks, and out of curiosity, keeps tearing the scab off a slowly healing wound, as if with the help of the mirror, this tired, worn-out pain could confirm her unity with her ego. And similarly to some serious cases of schizophrenia, when the regression of the personality is irreversible, all that the Art of Painting requires is its own company. By communicating with it during its lucid moments, the psychology of the former star is revealed to us. But all this is being written about in general art texts.

Paraphrasing Paul Virilio’s train of thought in the essay “The Origin of Forms”, one might ask, if we think about it more precisely, what has the golden age of painting, classical modernism, produced that is more unique and special than the expression of nothingness, absence. And this is clearly what Raus’s painting production is.

Hanno Soans

Sirp 18 August 1998