Capri

The Lotus-Eaters' Island

Capri has figuratively been compared to a sphinx, and its relief-like landscape truly is reminiscent of this fantastical beast. The legends associated with this tiny Tyrrhenian island are deeply rooted in history books. Opening these pages is like descending from Anacapri’s cliff along the Phoenician stairs to the turquoise sea surface below. For hundreds of years, these seemingly endless stairs were the only pathway that connected Capri, which contained the harbour permitting access to the mainland, to the nearly inaccessible Anacapri village located on a steep cliff plateau. Everything that was needed for daily life was brought up the meandering stairs and what was brought down was everything that Anacapri had to offer to the rest of the world.

The Phoenician stairs descend straight from the side of Axel Munthe’s Villa San Michele. A red speckled granite sphinx can be found keeping watch over the horizon on the terrace edge, as though it were guarding the city of Thebes in Sophocles’s tragedy, Oidipus. Unlike Oidipus, Munthe’s sphinx is from Egypt and is more of a benevolent guardian. With its lion’s body, bird wings and human face, the statue organically forms part of Munthe’s excellent staging of ‘stones’ from different eras that decorate Villa San Michele. Many of Axel Munthe’s ‘stones’ hold very symbolic meanings and it seems as though the doctor did not select them coincidentally. For example, knowing that Munthe used hypnosis as a form of treatment, it is fitting for the antique dream goddess Hypnose to stand above Munthe’s bed in his bedroom.

The relationship between the sphinx, which in Ancient Greek translates to ‘the strangler’, and Capri has historically been more than just symbolic. The connection has its origin in the Roman empire, which is when Capri became a retreat for a long period of time. Many dissidents who had lost the ruler’s favour were banished to Capri, where they would often meet their ends at the hands of assassins. One of the most famous of these was emperor Marcus Aurelius’ grandly deluded son, Commodus. In 182 AD, Commodus’ older sister, empress Lucilla, organised a failed conspiracy that sought to remove her brother from power. Commodus banished Lucilla to Capri, where he later had her murdered. A similar event occurred on the island but this time with Commodus’ banished wife, Crisipina. Much like in an Ancient Greek amphitheatre, life in Capri served as a fitting backdrop for these tragedies. Ancient Greek amphitheatres were typically built into nature that left beautiful views on the mountains or the sea open to be the stage’s backdrop. Plays were delivered to the audience and to the gods alike, who ruled over the human world as well as over forces of nature.

Although the first Roman emperor, Augustus, had already built his sea-side villa in Capri, the island only became the true centre of the world under the rule of his son-in-law, emperor Tiberius. Fearing conspiracies planned against him, Tiberius moved to the island and lived there from 26 AD to 37 AD, forming the island into a kind of fortress. He had twelve villas built there, the most famous of which was a villa dedicated to Jupiter, Jovis. The nearly 40 meters tall palace with 8 stories stood on an inaccessible rock that rose from the sea surface. In light of both architecture and engineering, Jupiter’s villa was a big accomplishment. As no water could reach the villa 300 meters high up on its tall vertical cliff, large reservoirs were constructed to capture rainwater. After being filtered, the rainwater supplied the Roman baths, fountains and gardens surrounding the palace with water. In the construction work, volcanic rock and a mixture of mortar were used. The lighthouse that was located on the villa’s highest point communicated with the Miseno military harbour through light signals, and hereby with the entire Roman empire.

Tiberius’ presence on the rocky island continues to be felt today and the remnants of buildings from his time are noticeable in many places. The most mysterious location on the island, the Blue Grotto, was also used during Tiberius’ time. Its exact function remains unknown but it is speculated that the Blue Grotto might have served as the emperor’s private swimming spot or perhaps as a Mithras cult cave.

A significant event that marked Tiberius’ time on Capri that changed world history and continues to influence it today was the crucifixion of Jesus Christ in Judea in 33 AD. Pontius Pilate ordered Jesus’ crucifixion and was a Judea prefect who Tiberius had appointed. Through a chain of command, Tiberius, the empire’s ruler, was aware of the events happening in Judea as well as Pontius Pilate’s activities there. Knowing Jesus’ life-story from gospel more or less from birth to death, it is possible to imagine the parallel world in which Tiberius lived in Capri where he ‘played’ with under-age boys in his Roman baths, whilst Jesus proclaimed his truth of love to Judea’s common people. Either way, Tiberius did not foresee that our outlook on the passage of time would change based on Jesus’ birth and that his proclamations would give rise to the religion that ultimately compromised the Roman empire. Least of all, Tiberius could not have foreseen that one of Jesus’ followers would become an all-mighty Roman emperor.

According to the gospel of Matthew, Jesus met Tiberius at least once. More specifically, he saw his profile on a Roman coin which a group of Pharisees showed him in a ploy to insidiously ask him whether or not they should pay taxes to the emperor. In response, Jesus asked whose name and picture was on the coin. Receiving his answer, Jesus replied that they should give the emperor to the emperor and give God his own coin. The Roman coin that the Pharisees displayed to Jesus contained an image of Tiberius with the text, ‘Emperor Tiberius Augustus, godly Augustus’ son.’

After Jesus’ crucifixion, Tiberius lived for another four years. Following his death, a new emperor entered the picture, called Caligula. He was Tiberius’ step-son who had been raised in the Capri court. It is speculated that in his final days, Caligula violently accelerated Tiberius’ death so as to rise to power quicker and to seek vengeance for the suffering Tiberius had inflicted on Caligula’s family. As a response to Caligula’s father, Germanicus, having become too popular a commander amongst the people, Tiberius ordered Germanicus to be cornered and killed on the infamous ‘poison path.’ Throughout history, Caligula’s tyrannical reign has been the source of plenty of inspiration for films and novels ranging across all kinds of genres. Directly before the end of World War II in 1944, one of the most famous of these got released - the French author Albert Camus’ play ‘Caligula’, which brought a past tyrant’s inner world into the present.

Stalin ruled the Soviet empire in a similar manner to Caligula, as he even kept spies on the far-away Capri in order to keep an eye on one of the most important Soviet authors, Maxim Gorky, who was hiding there. However, unlike Commodus, Stalin did not pay an assassin because he needed Gorky brought to him alive in the hopes that he could get a biography written about him. Despite previous praises he had written in the West about gulags and Stalin’s politics, Gorky was shocked by the actual reality of the ‘proletariat’ rule after he was finally coaxed into coming to Russia in 1932. As a result, he left the tyrant’s wish unfulfilled. Much like Lucilla in Capri, Gorky died under confusing circumstances inside the golden cage of house arrest. However, unlike Lucilla, the backdrop of Gorky’s death was not the beautiful deep blue horizon of the Tyrrhenian sea but was instead a grey Soviet Russia buried in mud and suffocating in smoke.

In Capri, a few decades prior to Gorky’s death, Gorky played chess with Lenin and other well-known Russian revolutionaries. For a few months in 1909, Gorky’s established Capri school operated as the top school for propaganda for the Working Class. The upcoming world communist revolution was planned under the name of Gorky’s school in Capri, which yielded terrible results felt by half of Europe and many subsequent generations. Gorky’s school in Capri took place just a few years after one the most powerful men of this time period stayed in Capri - the German steel manufacturer, Friedrich Alfred Krupp.

Krupp had a harbour, Marina Piccola, and a modern mansion built in Capri. Maxim Gorky stayed in that same villa which had been converted into a hotel, and that hotel terrace is where he and Lenin played chess. Krupp owned two luxurious yachts that were kept in Capri’s harbours, one of which was called Puritan. However, Krupp himself was far from being a puritan. In 1902, a Naples newsletter, Il Matinos, published an article about how Krupp, the well-known steel manufacturer, had been organising orgies in Capri with groups of young boys, and how his lover was a local 18-year barber. As a result of this scandalous news, similar articles emerged in German newspapers. Krupp’s spouse, Margarethe von Endele, received compromising photos of her husband’s activities in Capri, who then went on to complain to a family friend of theirs, Kaiser Wilhelm II.

The Kaiser understood that the development of Germany’s war industry was at stake. In the hopes of suppressing the scandal surrounding Krupp, Wilhelm II chose to send Krupp’s wife to a mental institution. However, this did not succeed in muffling talk of this scandal and instead, it gathered steam. Finally, Krupp, having returned to Germany in the meantime, committed suicide.

Some claim that Friedrich Alfred Krupp’s tragic story served as a source of inspiration for Thomas Mann’s ‘Death in Venice’ which was published several years following Krupp’s death. Krupp’s legacy in Capri can even be felt today in several ways. Almost symbolically, a paved footpath that connects Capri and Anacapri is named Via Krupp, which creeps along dangerous bends along steep cliffs.

A similar story to that of Krupp in Capri is that of the French novelist and poet, Jacques d’Adelswärd-Fersen. Through his father’s side, he was the descendant of the Swedish diplomat and count, Axel de Fersen. Axel de Fersen, who also had some Estonian roots, is foremost known for his attempt to rescue Marie Antoinette from the claws of revolutionaries during the French Revolution. Although his rescue attempt failed, the count and Marie Antoinette’s long-lasting romantic relations have been preserved in their passionate letter exchanges, which are regarded as some of the most beautiful love letters ever written.

Jacques d’Adelswärd-Fersen also possessed literary talent. Alongside poetry, he published the first international homosexual newletter in France, Academus. Amongst others, one of its featured authors was the ‘neighbouring’ Russian revolutionary from Capri, Maxim Gorky. In France, Jacques found himself facing accusations of pedophila. Fearing criminal charges, he escaped the scandal by fleeing to exile in Capri. In Capri, Jacques had the gorgeous Villa Lysis built. It is no coincidence that Villa Lysis stands next to the ruins of Tyberius’ villa, Villa Jovis. Differing little from Krupp, Jacques found a ‘faun’, a 15-year old newspaper vendor, Nino Cesarini, straight off of Rome Street. Jacques d’Adelswärd-Fersen brought back ‘lotus fruit’, an opiod, from his travels to Asia, which he used in his orgies. Using this in his orgies brought Capri back to Tyberius’ times. D'Adelswärd-Fersen's life ended in Capri in 1923, when he committed suicide by drinking a cocktail mixed with champagne and opioids. The literary legacy that he left behind forms part of Capri’s legends today.

Both Krupp and d’Adelswärd-Fersen lived in an era where homosexuality was illegal in Europe. For this reason, Oscar Wilde was sentenced to two years of imprisonment in 1895. Upon his release, he left his homeland for Naples, Italy. In Naples, Oscar Wilde and his partner, Alfred Douglas, planned an expedition to Capri to ‘lay flowers on Tyberius’ grave’. Wilde and Douglas stopped at one of Capri’s most famous hotels, the Grand Hotel Quisisana, but having recognised Oscar Wilde through the disguise of his false name, the hotel manager denied them their stay. The men were told to leave Capri immediately and were even denied their breakfast service.

Coincidentally, Douglas and Wilde bumped into Axel Munthe, who apologised on behalf of the island’s people for their unjust treatment of the writers, and kindly invited them to stay with him. Douglas and Wilde ended up staying in Capri for several days, enjoying Munthe’s hospitality in Villa San Michele. Doctor Axel Munthe, whose Phoenician stairs we began our descent from at the start of this story, had a completely different fate to the former two men.

Munthe was a world citizen who was multilingual; he could easily navigate his way around the upper society in both Paris as well as Rome; he felt at home in the Swedish royal court and in working class slums, and he healed poor patients and over-charged the rich so as to bring his vision of Villa San Michele to life. Many of Munthe’s medical methods were ahead of their time. In fighting illnesses, he considered the will-power of his patients and harmony between body and mind to be of great importance in his treatments. Munthe was also a big animal-lover and was one of the first to start advocating for animal rights. As an animal rights advocate, Munthe was against all forms of hunting and even turned to Mussolini to establish a hunting ban in Capri. Munthe had many friends and conversationalists who shared his views on animal rights, the closest of which was the Baltic-German scientist Jakob von Uexküll, who was born in Läänemaa Keblaste and had studied zoology at the University of Tartu. Von Uexküll also had a villa in Capri and was buried on the island.

One of Axel Munthe’s long-term friends, wards and lovers was the Swedish Queen Victoria. Queen Victoria seasonally lived in Capri for decades and shared values with the doctor. Together they walked, played music, and spent time with animals and art. With Queen Victoria’s financial support, Munthe bought Barbarossa hill in Capri which he turned into a bird sanctuary. Unfortunately, unlike Axel de Fersen and Marie Antoinette’s letters, no letter exchanges between Axel Munthe and Queen Victoria have survived. However, this story of friendship or romance was definitely one of Capri’s most romantic stories.

Having descended down the Phoenician stairs and having almost arrived at the sea surface, we could place an orange and black Ancient Greek vase on the bottom step, which would contrast beautifully with the turquoise blue sea. The vase would depict Odysseus tied to shipmast encircled by sirens as though by a flock of birds. This was one of the favourite motifs of Ancient Greek ceramics for Odyssey themed pieces.

According to legend, Odysseus arrived at Capri’s cliffs with his companions where he encountered lotus-eaters. Lotus flowers were an intoxicating, narcotic substance, and upon their ingestion, they would make one forget their home-sickness. Therefore, Odysseus had to use force to get his companions to leave the island and continue their search for their way home to Ithaka. He let himself be tied to a shipmast and stuffed his ears with beeswax plugs to prevent himself from being driven insane by the hypnotising songs sung by the encircling sirens and mermaids, which had driven him and his fellow-sailors mad.

Homer’s mermaids made an appearance in Danish author’s Hans Christian Andersen’s fairytale, The Little Mermaid. He visited Capri in 1835 and wrote his famous tale on the Little Mermaid a few years following his trip.

The ‘discovery’ of Italy and the start of the trend of Northern Europeans travelling to Italy can be attributed to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s travels to Italy between 1786 and 1788. These formed the premise for the report on his travels, ‘Italienische Reise’, which was published in 1816. Goethe’s travel journal held symbolic significance and after its publication, Italy had a fixed place in the travel itinerary of every educated person. Naples became a popular destination and through it, Capri was soon discovered. A significant German population grew on the island and by the end of the 19th century, a small German Lutheran church had even been established. Capri began to fascinate artists too and visiting the island became an unmissable destination on their Italian quests.

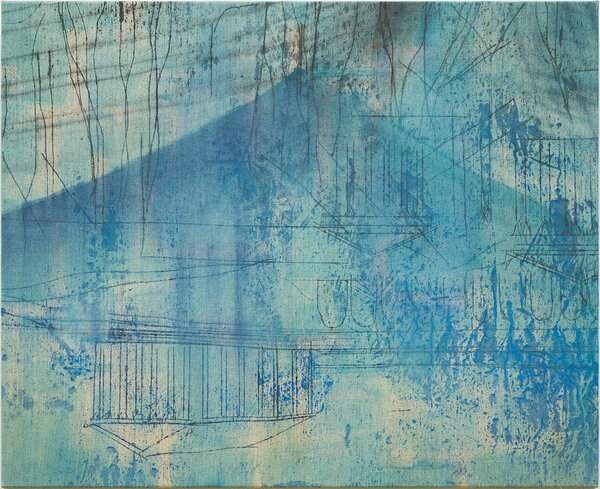

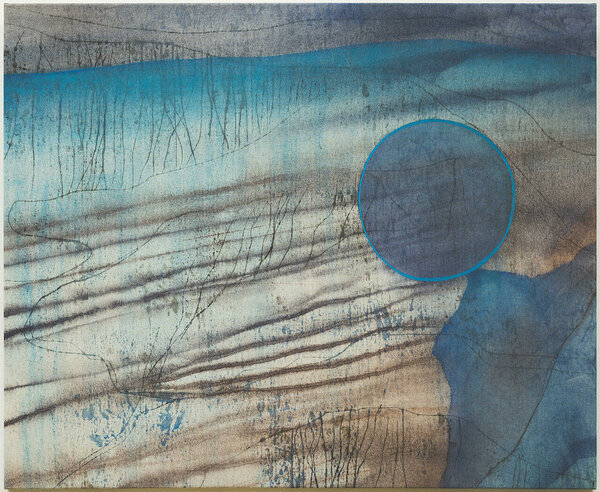

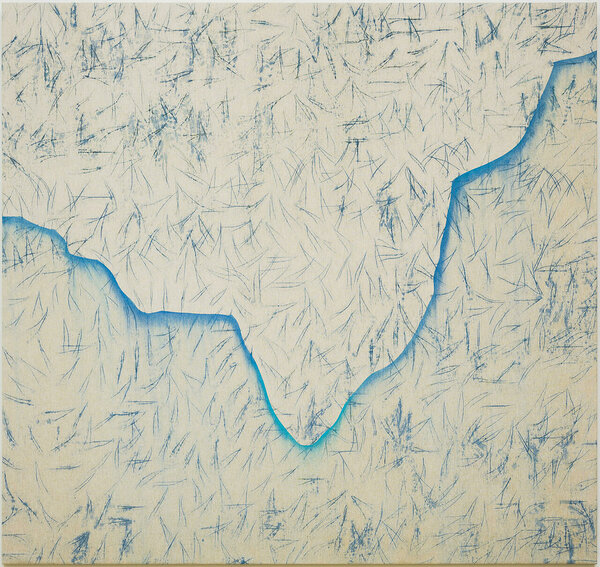

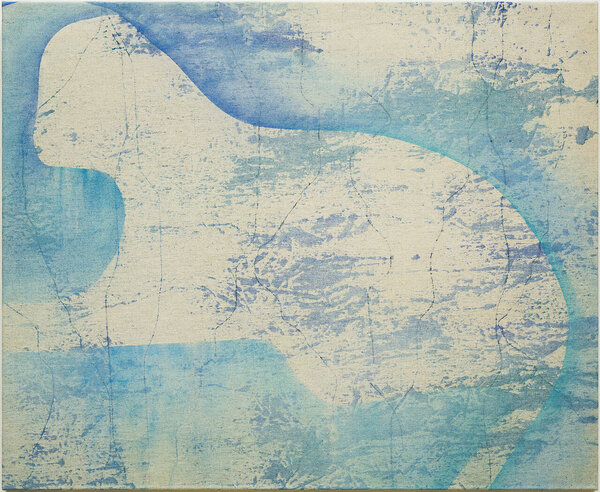

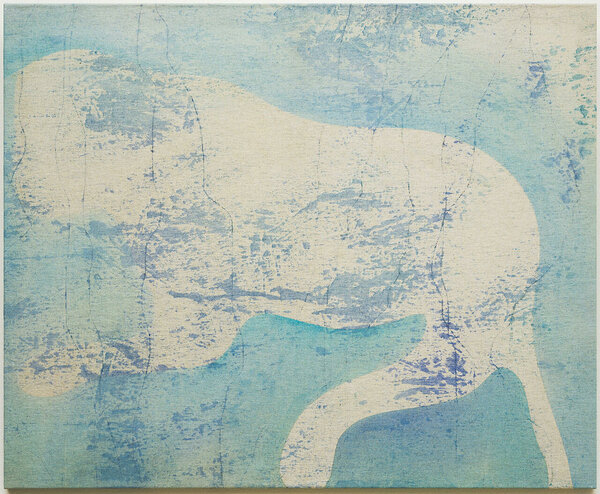

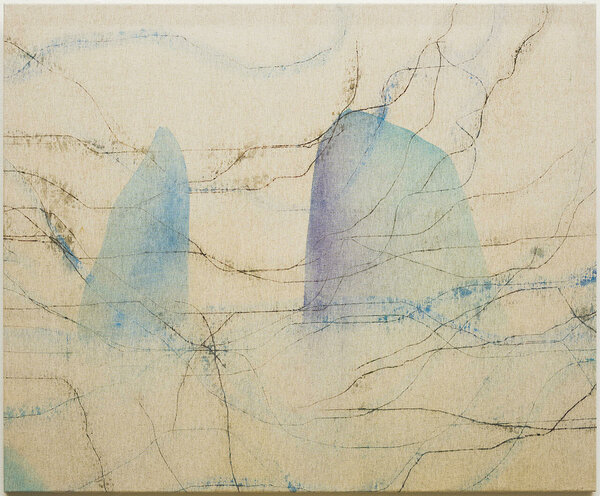

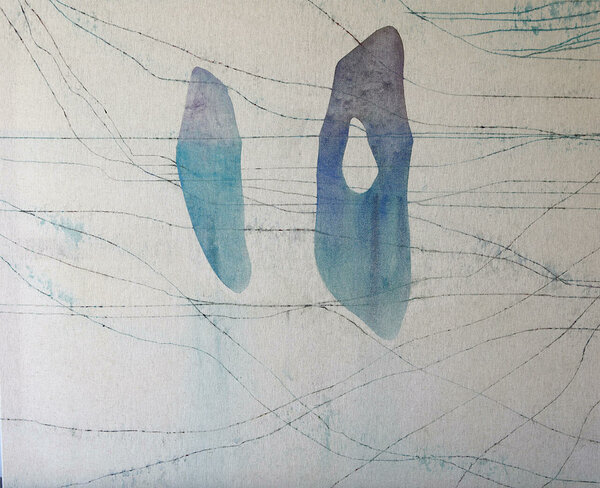

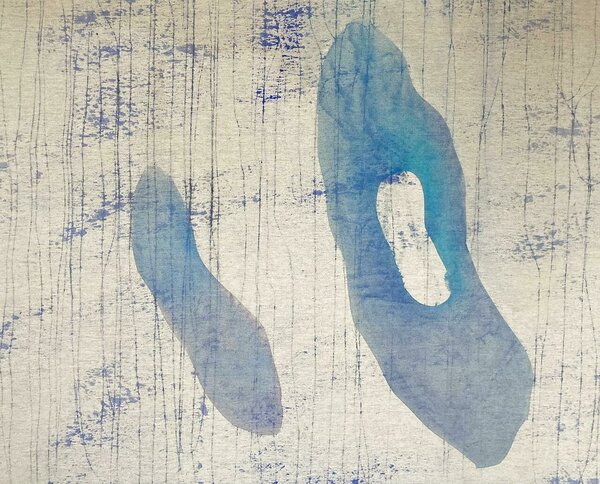

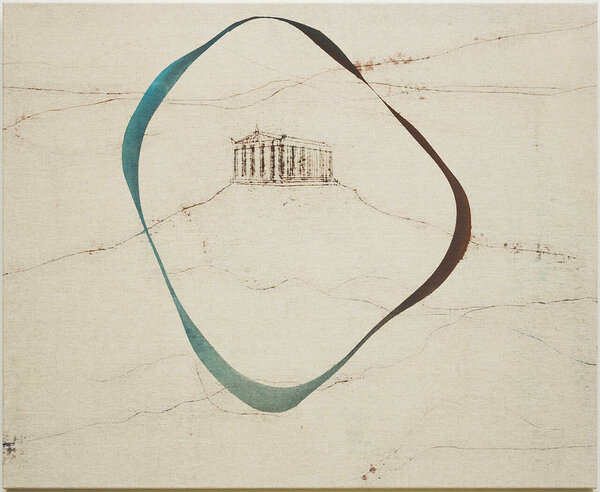

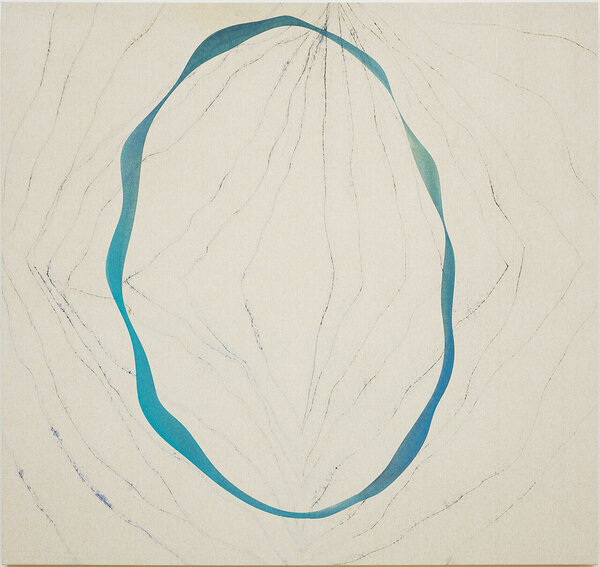

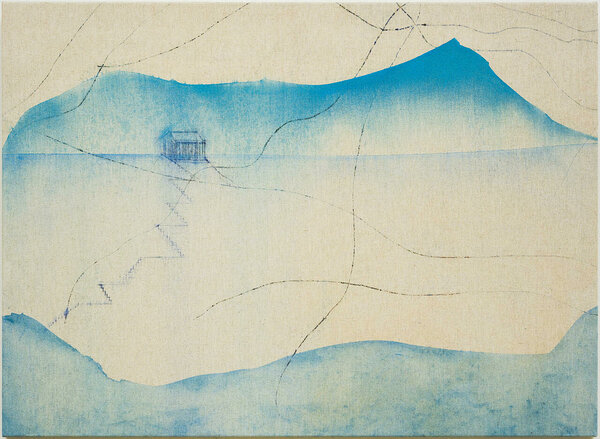

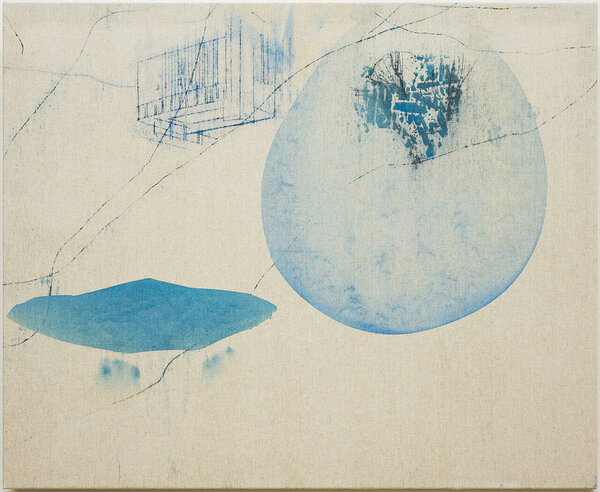

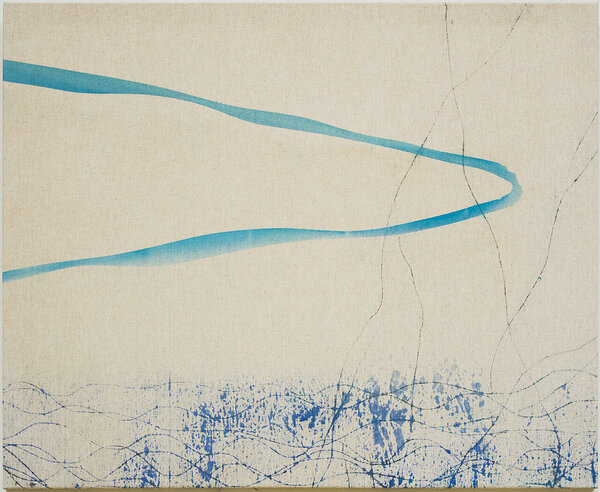

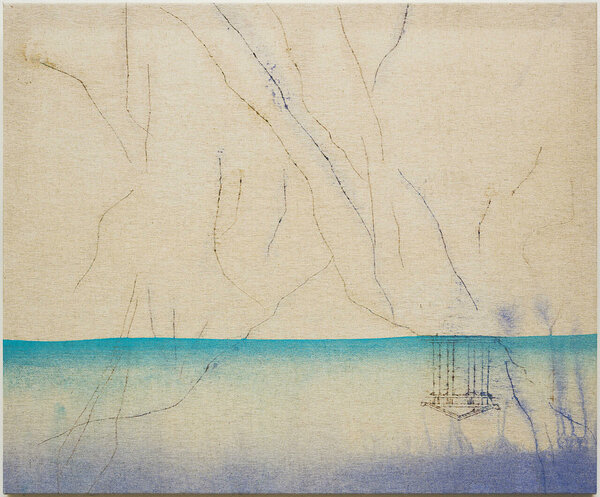

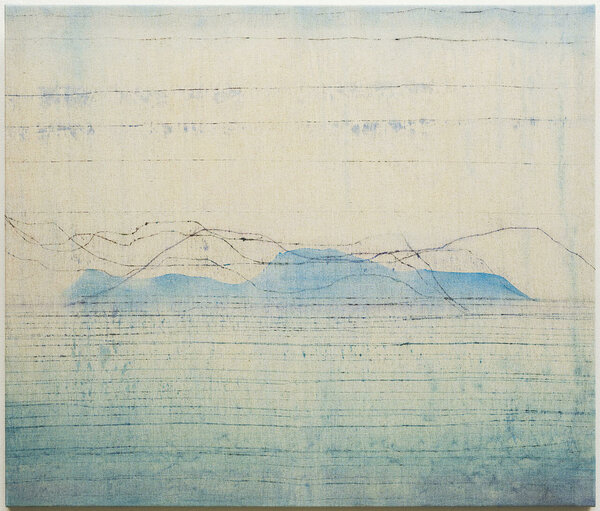

In 19th century Europe, people began discovering traditional Japanese and Chinese painting styles, the likes of which had never been seen before in Western European visual art.

In Eastern art, artistic composition builds a schematic journey. The artwork itself is a meditation or journey, which our eyes can travel across as though over a dream-like landscape. All that is depicted is symbolic and is based on natural elements. Behind its two dimensions, one can anticipate a different world whose depth the artist does not even attempt to imitate with precise perspective. When people are depicted on these nature paintings, they are small and are almost always traveling somewhere.

Since the Renaissance, Western-European art had been on a relatively one-way path of development. The fact that a big shift took place in the middle of the 19th century is directly connected to the discovery of new civilisations and their immediate influence. Actually, other civilisations made their way to Europe through Parisian art exhibitions. In order to see face masks from Africa and Oceania or Japanese and Chinese ink paintings, impoverished European artists did not necessarily need to travel to these far away places. In fact, this was a privilege few could indulge in at the time. All that was needed was to voyage to Paris, which could even be done on foot. However, if one wanted to see magnificent landscapes with one’s own eyes and if more resources were available for travel, then one would go to Europe’s furthest corner; Italy; to the foot of Mount Vesuvius, and to Capri.

Whilst sitting on the terrace of Axel Munthe’s Anacapri Villa, I realised that Capri’s vertical cliffs; Mount Vesuvius’ silhouette on the horizon, and the iridescent water element between the sky and sea were very similar to traditional Eastern paintings. All of the most important elements were present; the holy mountain of Fuji; the rising vertical cliffs with some pines growing from their sides; the water, and the special, deeply tinted fusion between the sky and sea. As for myself, I am but a traveler between those cliffs.

Urmo Raus 2021 Ⓒ

_block.jpg)